Text by Miguel A. López, 2022

Tania Bedriñana. El vestido al revés

Hecho el Depósito Legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú

ISBN 978-612-5062-11-6

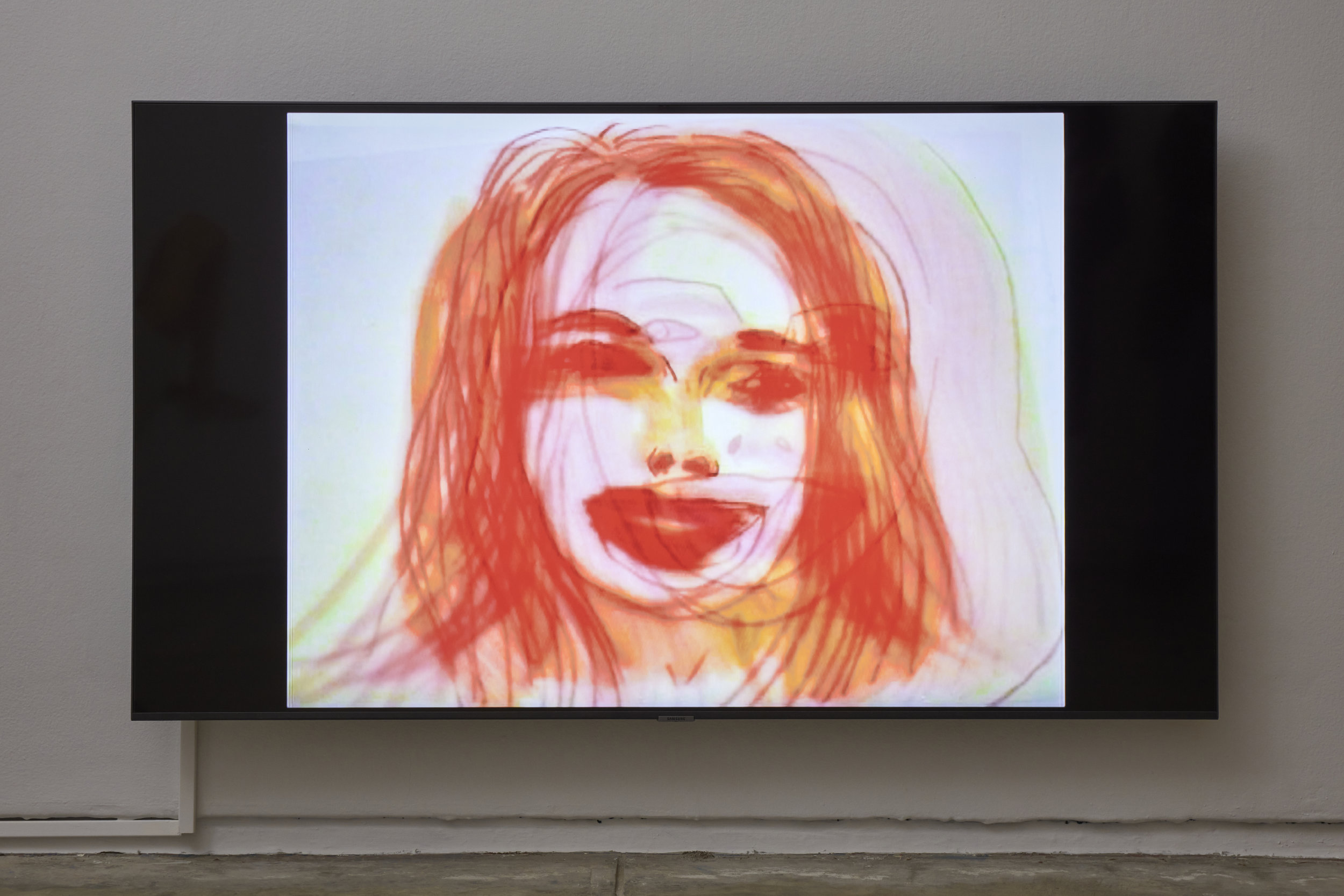

Tania Bedriñana has painted hair, skin, heads, fluids, arms, eyes, and tongues, all of which act as bridges between different places and times. Like a wizard or an alchemist, she turns a series of simple materials (paper, fabric, cardboard, pigments, and emulsions) into soft anatomies and fragmented bodies that occupy spaces as if new life had been breathed into them. Their physiognomies are simultaneously inside and outside. A mask that is a dress that is a blotch that is a hand that is a leaf that is an ear.

Her paintings, pottery, pencil drawings, cut-outs, and assemblages may seem at first glance like melancholy intimist landscapes, but one must look again—or cease to look only with the eyes. There is something uncertain and magnetic in her way of representing things, as if her lines were open questions about how our bodies make themselves visible and hide themselves in the world. Bedriñana’s works do not offer us soothing, tranquil spaces. Quite the opposite— they introduce us into a turbulent voyage where we find ourselves unpacking questions long concealed in the hidden corners where our worries and anxieties lie buried. The artist even leads us to doubt our own images of ourselves, as if the habitual representations of our faces—especially those taken from photographs— were nothing more than a fiction, a piece of theater. In response to that, the artist seems to assert that the task of painting is precisely to make space for and restore those uncomfortable sensations: to make our strange borders speak.

In her hands, art is a technology for producing anatomies that evade capture. As if there were nothing permanent, only mutations. Her work has typically been associated with an exploration of the childlike, of dreamlike universes, perhaps due to the constant proliferation of bodies with no defining signs of age and chromatic atmospheres that evoke thresholds of dream and fantasy. However, her figures go even further than that: Bedriñana depicts beings battling to escape the disciplinary logic that organizes the world—the domesticating effect of neoliberal education; the surveillance and norms regarding public behavior; the medical, legal, or psychiatric discourses that attempt to define who is (and isn’t) suitable for life. It comes as no surprise that the faces in her paintings lack any defined features. The eye sockets are nearly always empty, the contours of the skin consist of unfinished lines, and the scenes surrounding the bodies are often hazy, combining dense and diluted pigments.

This essay proposes to connect two important moments in her work: on the one hand, her little-known beginnings in the mid-nineties in Lima, as well as her move to Germany in 1999, where her work consolidated a defined interest in fragmentation and paper cutting; and on the other, her more recent output, after an intense series of visits to Peru since 2018. The way in which her painting has been interpreted has also changed along with the emergence of social processes which have challenged patriarchal cultural values, something that had long made it difficult to grasp the complexity of certain aesthetics and forms of representation. For over twenty-five years, Bedriñana has engaged in a rigorous work that we can only now begin to understand in its true magnitude.

For the artist, painting has been a space for introspective exploration that acts as a thermometer of the things that help us to keep ourselves alive in a profoundly violent social setting. Indeed, her images return us to a different state of matter: gaseous oscillations or liquid atmospheres that shatter the arrogance with which we typically see our bodies as closed containers free of cracks, whole and impenetrable. And while there are many images from the past that float through her works, the artist does not propose mere nostalgic revisitations but instead seeks to respond to how those recollections behave today in her body: hers is a work of the present.

The early years

Her pictorial work has always been associated with the exploration of the human form. Bedriñana was never interested in reflecting the physical characteristics of the body, but rather touching on the fleeting sensations that typically go unnoticed by subjects themselves. After graduating from the Universidad Católica Art School in 1995, the artist created a series of largescale easel paintings as well as a more intimate output of a smaller size, made with tempera and ink on paper. These changes in scale were tied to important transformations in her life, such as moving out of her family’s home to live on her own. That move impregnated her work with question marks linked to the uncertainties of adult life, loneliness, her place as an artist, and the hostility of a misogynist, racist city.

Another of the key aspects in her oeuvre is the constant representation of female bodies.While various images seem to evoke her own face and body— one is tempted to see in them an incessant repertoire of self-portraits, each one more complex than the last—the artist has said multiple times that she is not trying to portray specific people. In fact, her painting seems to evince a desire to represent emotions shared by many women—women from her generation, but not only. Recalling the conversations she had with her girlfriends in the late nineties, which also set the tone for various of her paintings, she says, “All of them felt something similar: a lurking unease, a sense of uncertainty. We always talked about leaving, going somewhere, anywhere.”One of the effects of neoliberal capitalism’s triumph has been to turn social problems into individual issues, reducing the complexity of certain ills to only psychological pathologies

rather than recognizing them as political problems derived from violent class structures, patriarchal logics, and forms of colonial dispossession. The feeling that one has no place in society is inevitably linked to a matrix of power. The British writer and cultural critic Mark Fisher describes it clearly:

For those who from birth are taught to think of themselves as lesser, the acquisition of qualifications or wealth will seldom be sufficient to erase— either in their own minds or in the minds of others—the primordial sense of worthlessness that marks them so early in life. Someone who moves out of the social sphere they are “supposed” to occupy is always in danger of being overcome by feelings of vertigo, panic, and horror.

Bedriñana’s work seems to have a keen grasp on that invisibilized space in which we are pushed into believing that the emotional pain and existential malaise we feel is our own responsibility. Her images invite us to navigate through certain shared feelings, oftentimes associated with silent (and silenced) structures of male violence. Nor is it an accident that her depictions of women serve as forms on which to project herself: not self-portraits, but attempts to exist outside her own body, or perhaps ways of distancing herself to understand who and where one is.

In Peru’s art scene, the nineties were an ebullient moment of response to patriarchal violence, although it was not yet named as such. During that decade, feminisms had not yet forcefully permeated the artistic field, a situation that would not begin to change until the first few years of the new millennium. In spite of this, the works of numerous artists and feminized bodies denounced misogyny, although without congealing into a current or organized movement. These images emerged from different (aesthetic, social, geographic) positions, and even without any direct dialogue between their creators, both inside and outside Lima’s artistic mainstream. Some of these processes were recently revisited in the exhibition “Hay algo incomestible en la garganta. Poéticas antipatriarcales y nueva escena en los años noventa” (“Hard to Swallow: Anti-patriarchal Poetics and the New Scene in the Nineties”), which brought together nearly two hundred representations that shared a determination to disrupt the patriarchal common sense of a reality that was not only intolerable, but also difficult to capture using the language available at that time.In those years, the self-portrait became a powerful tool of analysis, as in the work of Gilda Mantilla, Susana Torres, Giuliana Migliori, Elena Tejada-Herrera, Patssy Higuchi, Natalia Iguiñiz, and Claudia Coca. Their images challenged the androcentric discourse and interrogated the woman’s place as a political subject. While the self-portrait had been used in various ways prior to that, in the nineties this profusion of self-representation erupted into the public debate, where it was typically interpreted as a form of hedonism and individualistic navel-gazing.In hindsight, however, it can be argued that the artists’ desire to represent their bodies was a way of reclaiming them as their own in the face of male authority, in a context where misogyny was also an extension of the Fujimori dictatorship.The same thing occurred in sculpture: using humor and irony, the sculptures of Cristina Planas elaborated upon female stereotypes, migration, history, and social violence, while the early work of Claudia Salem called for an undomesticated way of presenting the female body, as in an early installation in the gardens of the Universidad Católica featuring a nude self- portrait surrounded by flowers and other elements. Documentary photography also helped concentrate on insufficiently discussed aspects of the visual arts, as in Madres niñas (Child Mothers) (1999-2000), a series by Mayu Mohanna focused on teen pregnancy. Her photographs, taken in the Mother’s Hospital in Lima, collected images and testimonies from young girls and teenagers, typically migrants from the provinces, who were dealing with pregnancies resulting from rape and domestic violence, forced to become mothers while living in poverty- stricken conditions. The precariousness of life—the violence of childbirth and the difficulties these young women were going to face as mothers—clearly points to the ways economic violence—the class structure that determines access to health care—was a normalized form of control over women.

The aforementioned artists never shared exhibition spaces with Bedriñana. They didn’t know each other well, nor were they reference points for her work. Bedriñana’s oeuvre was developed along a parallel path, outside of the curatorial discourses that were most visibly shaping the cultural discussion during that decade. Her first works after graduating from the university were large oil paintings, including diptychs in the shape of a cross, as well as circular pieces. These were exhibited in her solo show “Pinturas” (“Paintings”) at the gallery Quadro in 1997. At the same time, she created an extensive series of small drawings and paintings on paper, made using washes and light brushstrokes, which were not intended to be exhibited and remained unseen by the general public until fairly recently.This fact is telling: university education and the art scene in general were gripped by the prevailing idea that drawing was an inferior language to painting. The force of that prejudice had caused artists such as Teresa Burga to decide, in previous decades, not to publicly show the hundreds of impressive drawings she had made in the nineteen seventies in which she explored her everyday life, the media, wage labor, time, and the representation of the female body.In recent years, these conservative parameters have begun to change, making it possible to address the complexity of a language that was ignored up until two decades ago, while also opening up a space for a different understanding of Bedriñana’s work.

In her small paintings from those years, women are often shown in assertive, defiant attitudes. While the internal armed conflict and the Fujimori dictatorship forged an atmosphere of extreme violence and collective despair, the most intense feelings of pain for the artist in those years came not so much from external agents but from an internal place: family memories that reverberated within her body without her being fully conscious of them. Moving into her own apartment gave her a space of autonomy that allowed her to reconsider the origins of this constant malaise and progressively escape a socially induced condition of individual culpability. Her paintings were an important site of personal exploration. Created with the speed and fluidity allowed by tempera, oil pastel, and ink, these works captured a series of emotions that were still difficult to verbalize at that time.

The first piece she painted after moving out was Hoyo negro (Black Hole) (1996). The work speaks volumes. On the right, we see the profile of a female face created using light colors. However, the brain is shown exposed in this portrait: the drawing of a pink gland that sticks up disturbingly above the hair, on which the artist has painted the divisions of the cerebral cortex. The face is crisscrossed by various vertical lines, one of which runs through her eye like a large tear trailing down her cheek. On the left side, a big black spiral absorbs everything around it, occupying almost two-thirds of the paper. Above that great gray cloud, the artist wrote the phrase, “Te presento a mi hoyo negro” (“I’d like to introduce you to my black hole”). The monochromatic severity stands in contrast to the colorful depiction of the woman. Although seemingly camouflaged in irony, the work declares a nebulous sort of anguish that invades and paralyzes everything. According to the artist herself, it was not so much the terror of political violence that resonated as strongly as the “fear of the mind itself”—a panic embodied by oneself that seemed to stem from one’s very being, the result of experiencing so many moments of class, racial and gender violence sedimented in daily life.

An examination of those early moments in which the artist worked at a smaller scale is key to understanding the changes that her oeuvre would undergo after leaving Peru. Bedriñana moved to Germany in 1999, where she studied for two years at Kunsthochschule Kassel before moving to Berlin in 2001, where she still lives today.In Germany, Bedriñana strove to take the possibilities and bounds of her painting ever further. The renunciation of the traditional support—the canvas on the easel—which was foretold in her works from the late nineties would become consolidated in those years. At Kassel, the artist began to experiment with translucent pictorial material, playing with paper fragmentation and different levels of opacity with watercolor and gouache that allowed her to achieve sensations of levity in the bodies she depicted. In Berlin, her work shifted toward the creation of cut-outs emulating body fragments, painted with oils and emulsions, which started to escape their place on the walls and generate three-dimensional experiences. Her human silhouettes sometimes appeared stuck together like a collage, or with their surfaces scraped away. As if the skin had been torn from the bodies, these fragments composed choreographies that were sometimes tender yet disturbing. One of the characteristics of this new period was the ability to create multiple compositions: the elements were displayed hanging, placed on the ground, or superimposed on one another, always offering the possibility for subsequent reorganization and assembly in a different way. These figures also shared a material quality of fragility, evoking the vulnerability of our bodies and lives.

Bedriñana played not just with cut-outs, but with space itself, painting scenes on the walls, as if it were a great fresco, suggesting a continuity with her paintings. As noted by the curator Gabriela Germaná (2017), while these forms appeared “almost by accident,” their composition and montage later involved “a work of great precision.” It was not only a question of what the fragments communicated, but the distance between them: the gaps, the way they depended on one another or rejected each another. Underscoring the sensual aspect of her installations, the German curator Harm Lux (2006) has offered a brilliant description of the way in which Bedriñana composes in space: “This procedure leads one shape to tell, first and foremost, a story; another [piece of paper] wants to ‘breathe’ first; yet another, for instance, emphasizes first its sculptural form, and only then, by virtue of the holes present in it, that which is missing.”

This process redefined the way she spatialized her pictorial practice, conceiving of it as a scene of connections and fragments which present life as a series of puzzles filled with a pain that is both private and social at the same time. Her first public exhibition in Germany was held upon completing her Freie Kunst degree at Kunsthochschule Kassel, where her professors included the artists Dorothee von Windheim and Norbert Radermacher. At the Stellwerk del Kulturbahnhof Kassel, Bedriñana presented her second solo show titled Alas de mariposa (Butterfly Wings) (2002), a complex and ambitious installation that included numerous cut-out figures on the wall, watercolors on paper, and a video animation.The work elaborates upon emotional changes and the experience of the female body during puberty. While several of the small scenes and images were inspired by personal memories, the installation was not necessarily an autobiographical statement. Bedriñana painted numerous faces, hands, feet, and other fragmented body parts, depicted colorful flowers and clothing, as well as pieces that alluded to paternalism and male authoritarianism, such as a silhouette of a female body standing on the palm of a large, outstretched hand.

One important aspect during those years was the relationship that the artist began to develop with her own dreams and nightmares. The act of painting was a way to keep from entirely losing those images and symbols, inevitably ephemeral. The artist describes it as “the need to trap that fleeting instant of unconscious reality that starts to escape upon waking, as if in a kind of delirium.”The video animation was handmade by superimposing drawings, records of her dream experiences rendered on transparent paper. This is the only audiovisual piece that Bedriñana has created to date, offering a hypnotic, spellbinding personal journey in which the very bounds of reality are blurred.

The emergence of cut-outs figures during those years was not only a chance for Bedriñana to deploy new ways of painting, but to talk about the fingerprints left on us by our family in such a way that we feel physically defied by that fragmentation. The artist breaks apart bodies to make audible the complex emotions that navigate the intersection between affectivity and violence, enthusiasm and anguish, silencing and memory.

Recent years

Her departure from Peru shortly after graduating and her decision to permanently settle in Berlin led to an inevitable distance from the local art scene. Between 2002 and 2017, her work was mainly shown in Germany, with a limited number of appearances in Peru. Her second individual exhibition in Lima, titled “Personanormal” (“Abnormalperson”) (Galería Forum, 2007), occurred nearly a decade after her leave-taking. Five years after that, she presented the solo show “Enfant terrible” (Galería ICPNA, 2012). In these appearances, Bedriñana’s work had no clear reference point in the Lima scene. Her movement between abstraction and the human figure, and her desire to portray not people but emotions, had no obvious counterparts in a context where recent painting has always had one foot strongly anchored in the exploration of more explicit references, whether in themes associated with the landscape, the national imaginary, family history, political memory, or the like. The way in which Bedriñana’s work arrives at a language of the installation while reclaiming the pictorial is also unusual and proved difficult to process for a local art market accustomed to painting on canvas.

At the international level, her work seems to share certain traits with the output of artists such as Marlene Dumas (based in the Netherlands) or Miriam Cahn (based in Switzerland), who have developed powerful repertoires of bodies with ghostly qualities. Depicting ambiguous anatomical shapes, the paintings of Dumas and Cahn confront society’s homogenization. Both combine techniques of fluid painting and denser pigmentations to create an atmosphere of estrangement which straddles the descriptive and the suggestive. While Bedriñana utilizes these blotches created with a wash technique, the difference lies in the punctured tear and a certain degree of chaos in the surface of her painting which acts as a foundation on which to compose. Sometimes it is unclear whether we are looking at what the artist has represented or if we are witnessing the glimmer of a wound of our own. The artist also shares with Dumas and Cahn the desire to capture a sense of danger: an intuition that something sinister has happened or is about to happen that is manifested in the ethereal, vibrant, or hazy colors that cover up and extend beyond the boundaries of the bodies.

The more dynamic link that the artist has established with the local art scene since 2018 has influenced her recent work. She has presented three successive individual exhibitions in Lima: “Umbra” at the Socorro Polivalente space in 2018; “Cortar el aire – Recorte contemporáneo” (“Slicing the Air – Contemporary Papercutting”) at the Museo de Arte de San Marcos in 2019; and “Hablo un borde extraño” (“I Speak a Strange Edge”) at Galería del Paseo in 2021.She has alsotaken part in group shows, such as “Hay algo incomestible en la garganta” (“Hard to Swallow”) (2021) and “Creadoras” (“Women Creators”) (2019), allowing her to engage in a dialogue with her female contemporaries. For the artist, this has meant constant trips to Lima and other places in Peru, bringing about renewed encounters with sensations and geographies that have helped shape some of her newer images. A long trip through the Andes in 2019 was especially important for her. “The saturated colors found in nature and the intense light entered inside me through my retina. I felt a physical change, an enormous relief,” she says (Villasmil, 2021).

From her immersion in the humidity of the cloud forests to the sun’s reflection on the stepped terraces used to let water evaporate and leave behind the pink salt of Maras, near Cusco, these sensations have brought up personal memories and the question of where and how one belongs. Bedriñana also learned new stories about her paternal grandfather, a peasant from Ayacucho, who died during a mudslide when he was swept over the edge of a precipice along with his teenage granddaughter. The artist was profoundly impacted by the knowledge that his body was never found, especially in a country where the erasure of the indigenous population and Andean culture has been part of Peru’s foundation as a modern nation-state project.

Several of her recent paintings have taken on a luminous intensity in which the landscape claims a leading role it had lacked in her previous series. Bedriñana has turned toward the representation of mountains, rivers, and the force of the wind. In Andes (2021), a nude girl is shown running while surrounded by green mountains. The image suggests an organic continuity between the body and its natural surroundings, but there are elements in the landscape that are charged with anguish and distress, such as the group of clouds that hang above a piercingly red sky. Other pieces allude to collective grief, such as Adiós (Goodbye) (2020), in which three figures attend a wake in the midst of a reddish landscape, surrounded by small clouds. The bodies occupy a tiny fraction of the full scene, mere shadows in the humid atmosphere:bodies with no specific traits that remind us once more of a violent history of deaths and disappearances

whose wounds have yet to close.

Some of her paintings, such as Ciempiés desnudo (Nude Centipede) (2021) or Piedras y flores (Stones and Flowers) (2021), suggest the presence of stratigraphic diagrams in which layers of color seem to gouge the figures’ skin. Bedriñana paints like someone engaged in an archaeological exercise, indirectly emphasizing the idea that we are an accumulation of overlaid strata, each one contaminating the others’ meanings. The artist’s fascination with masks is perhaps tied to the very possibility of losing or hiding one’s face, something that many people and communities must do every day to navigate the structures of class-based, patriarchal, racial, and heteronormative violence that comprise the world. Many have resorted to using a number of masks, reconstructing the anatomy and inventing a new repertoire of gestures to handle norms that discipline, classify, and pathologize bodies and their behaviors—norms that define the possibilities of access and representation available to subjects who historically have been marked as subaltern.

In recent years, Bedriñana’s work has also featured a noticeable return to the domestic space and parental relations. In the painting Huérfanas (Orphan Girls) (2020), the artist creates a green setting in which we see three female silhouettes: two little girls and a teenager. The bodies are shown looking at the horizon in an attitude of surprise, as if awaiting an imminent event. These works contain hints of some of the artist’s previous works, where childhood appears not as a safe place and a refuge, but as something that is beyond all control. Using pastels, Bedriñana made in 2015 a series of large scale drawings that revolve around the theme of children at play, forging a collision between the sensation of freedom—an autonomy that one slowly wins for oneself—and the kinds of threats that organize the world. In Cuidados de madre (A Mother’s Care) (2015), five worry-free girls seem to play while two of them carry small bundles that appear to be babies. The way they return the viewer’s gaze creates emotions of tenderness and discomposure. In Naufragio (Shipwreck) (2015), a female figure embraces two young girls in the middle of a raging storm. Bedriñana blurs their bodies to the point of fusing them with the rain and the orange water that appear to cover part of their legs. The sensation that everything is becoming filled with water evokes an unspeakable form of anguish. The exploration of the mother/ daughter relationship has been present in her work since the late 1990s, also taking the form of smaller drawings like Madre (Mother) (2007), rendered in charcoal, where we see three young girls situated around an adult woman lying on the ground, although we have no way of knowing whether she is ill or just playing. Elsewhere, her portfolios of drawings made with colored grease pencils in 2013 and 2016 capture emotions in movement, diffuse, fleeting, that attest to the ways all of us negotiate the place and territory we inhabit. Sensations such as disequilibrium or vertigo appear in tension with the ideals of calm and stability with which we have been taught to identify.

The creation of installations with fragments and cut-outs has remained an important part of her work. De mi barro (Of My Clay) (2021-2022) presents a combination of feminine silhouettes that are indirectly taken from family memories, although the faces are shown as indistinguishable blotches. One of them displays the image of a girl taking her mother by the hand, urging her to accompany her. There is a latent sensation of what the adult presence means from a child’s perspective. The presence of fragments of hands in the work offers a subtle reflection on creative alchemy: hands as tools that permit the creation of new universes, something that also involves companionship, caresses, raising children, and caring for them. The very title suggests the origin story of the human as being modeled from clay, although in this case it includes filial connotations: we are made from the clay of others, and it is to the soil that we shall return. As in her previous installations, Bedriñana projects her concerns, demands, and desires onto this floating group of silhouettes and paper skins stuck on fabrics, coarse cotton cloth, and linens which arise from their own clay—their own body.

Reclaiming one’s own body also involves recognizing it as a public space and a place in constant dispute. As the feminist philosopher Judith Butler reminds us, “Although we struggle for rights over our own bodies, the very bodies for which we struggle are not quite ever our own. The body has its invariably public dimension. Constituted as a social phenomenon in the public sphere, my body is and is not mine.” (2006, p. 41). The author is not trying to ignore bodily autonomy, but to emphasize the role that certain norms play in social life, which makes the lives of certain bodies livable while many other people experience dynamics of violence, extraction, devastation, and plundering on a daily basis.

Bedriñana’s works are portals that reveal emotional states and call attention to broader social structures. There is also a constant sensation of estrangement: her atmospheres raise questions regarding affective equilibrium, interpersonal exchanges, mental health, and our bonds with our personal memories. The artist creates a conflict in painting: she makes the angles, edges, and contours of our bodies speak. Her paintings manage to make an ear sprout from a hand from a blotch from a dress from a stone from a mask. They invite us to recognize ourselves as bodies/borders in a world that punishes deviation.

![Doble Sombra, installation, 2021. In: Premio ICPNA Arte Contemporáneo [ICPNA Contemporary Art Preis-Exhibition of finalists]. Pigments and emulsions on paper, cute and folded, montage variable, area 148 x 134 x 70 cm](https://taniabedrinana.com/wp-content/uploads/icpna_pac2021_tbedrinana_03_.jpg)